Easter Island (or Rapa Nui) has continuously drawn the attention of the scientific community since it was first sighed by Dutch Sailors in 1722. By those early days it was already described as a mysterious and isolated islet boasting hundreds of monumental stone statue –the Moais– and as the only island of the South Pacific that was completely deforested.

The iconic Moais of Rapa Nui called the attention of the European sailors that firs visited the island during the 18th century. The stone statues contrast with the highly eroded and deforested landscape. Photo courtesy of Nicolas de Camaret.

Many of these early mysteries are still debated, and there has been an ongoing interest in understanding its environmental history; not only for the potential of developing terrestrial reconstruction in a remote and isolated island in the middle of the South Pacific – possibly providing a link between the southwest and southeast Pacific, but also because of the fascinating analogies to our own isolated and resource-limited world (1).

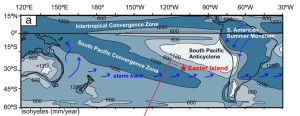

The position of Easter Island in the South Pacific and the main atmospheric component of the region. Map from Margalef et al. (2013).

Despite the long-lasting scientific attention, the environmental history of the island is poorly understood. Available proxy reconstructions have been mainly based on pollen analyses on sediment cores retrieved from the water-filled volcanic craters that border the island, and from macroscopic plant identification coming from various surface sites. However, the records have been dogged by stratigraphic gaps, dating problems and contradictory data, allowing for a range of interpretations.

An article published this year (2) presents the oldest terrestrial record published so far. Their reconstruction is based on a complete geochemical and mineralogical analysis of two sediment cores retrieved from a small peat bog located in one of the island’s crater slopes, plus a set of 27 AMS 14C dates. Changes in the chemical composition and accumulation rates of peat facies are used to infer changes in precipitation and temperature in the island over the last 70,000 years. Relative high (low) peat accumulation (oxidation) between 70,000-42,000 cal yr BP (MIS 4 and early MIS 3) is interpreted as increased rainfall and relative warm temperatures, while the opposite trend is observed between 40,000-31,000 (late MIS 3). Low temperatures and substantial rainfall are recorded between 27,000-18,000 cal yr BP (MIS 2). The authors attribute these climate variations to the interaction of different climate components, including north/south movements of the Southern Ocean and the Westerly Winds (SWW), and east/west shifts of the South Pacific Convergence Zone and the South Pacific Anticyclone (SPA).

This new reconstruction also provides interesting details of the island ecological history. Well preserved remains of the extant Totora reed (Scirpus californicus), a popular South American species of the bullrush family, suggest that this species have been present on the Island for at least 45,000 year. Its arrival is attributed to be windblown from South America (Totora is found in the self-made floating islands where Uru people dwell in Lake Titicaca, Bolivia).

Another recent reconstruction provides clues about the environmental histories of Easter Island during the Holocene, including early Polynesian arrival (3). In this case the proxy information is based on pollen, charcoal and plant macrofossils analyses from a AMS dated lake sequence that extend back for about 7500 years. This study highlights an apparently extended dried period that ended sometime before 750 cal yr BP. Based on present-day climate controls, the authors argue for centennial-scale southward shifts of the SPA (and the SWW) as the main driver for this prehistoric drought, a similar atmospheric configuration behind present-day annual droughts in the central coast of Chile.

Overall these new records illustrate the sensitivity of Eastern Island to the large-scale climate variations that characterized the late Quaternary, and provide new evidence on the poorly understood climate history of the Southern Pacific. The ecological responses of the Rapa Nui to past climate changes, however, pales in comparison with the intensive process of deforestation, wild burning and erosion that dramatically change the landscape of the island soon after Polynesian arrival by about 750 cal yr BP, but I’ll save that for another blog entry…

References

- Diamond, J., 2007. Easter Island Revisited. Science 317, 1692-1694.

- Margalef, O., Cañellas-Boltà, N., Pla-Rabes, S., Giralt, S., Pueyo, J.J., Joosten, H., Rull, V., Buchaca, T., Hernández, A., Valero-Garcés, B.L., Moreno, A., Sáez, A., 2013. A 70,000 year multiproxy record of climatic and environmental change from Rano Aroi peatland (Easter Island). Global and Planetary Change 108, 72-84.

- Mann, D., Edwards, J., Chase, J., Beck, W., Reanier, R., Mass, M., Finney, B., Loret, J., 2008. Drought, vegetation change, and human history on Rapa Nui (Isla de Pascua, Easter Island). Quaternary Research 69, 16-28.